A recent update of our study on the carbon footprint of nations highlights the role of China, Russia, the USA and the EU.

Steven Davis and Ken Caldeira have just published an analysis of the carbon footprint of nations using the GTAP 7 database, allowing for a comparison of the years 2004 and 2001. The paper published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS for short) uses the same methods, research questions and data sources as our 2008 and 2009 papers. It highlights the role of the most important polluters and largest trade flows by emissions embodiment.

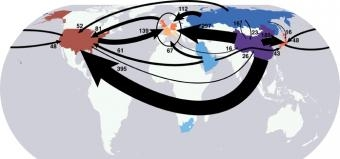

According to Davis and Caldeira, 23% of the global CO2 emissions from fossil fuel burning were connected to the production of goods ultimately consumed in a different country. The largest trade flows in terms of pollution required to produce the goods traded (embodied emissions) were from China to the United States, Europe, and Japan. The flows from Russia at Europe and from the Arab Middle East to EU and US were also significant, as was the trade between US and EU (see figure).

News stories on the article in the New Scientist and the BBC emphasize the point that many European countries have a larger difference in emissions between the consumption and production perspectives than the United States, measured per capita. In other words, the difference in emissions embodied in imports and emissions embodied in exports is larger. In my opinion, this is really not a relevant way of interpreting the results. What counts is the fraction of the national carbon footprint (consumption based emissions) outsourced to other countries. Europe can hardly be criticized for having a much lower emissions intensity than the United States, which is the reason for why the net trade balance is higher for the EU than the US.

I think that Davis and Caldeira do a particularly nice job highlighting the increasing specialization of production in the global economy and the differences in the imports and exports of different countries. It is striking that the emissions intensity of exports from Russia, China and India are more than 2 kg of CO2 per $ traded, while those of European countries listed are between 0.17 and 0.25 kg per $. The reason for this difference is most likely a combination of the difference in the emissions intensity of the energy mix, the energy efficiency and the value of the products produced.

The split of emissions embodied in trade by traded commodities also indicates the importance of global value chains. The largest flows for most countries shown are “intermediate goods”. The logical next step will be to investigate the makeup of global value chains, analyzing the through-trade of carbon of countries. Given global value chains, how are the carbon footprints of specific products distributed across countries?

Davis and Caldeira did not go through the trouble of adding the emissions of non-CO2 greenhouse gases and could also not assess emissions from land use change. As a result, the emissions in some poor countries are very low – 0.12 tons per capita in Ethiopia and Malawi, compared to 22 tons per capita in the United States. As we have observed in our analysis, for such poor countries, the emissions of methane and nitrous oxide from food production are much more important than the emissions of CO2 from fossil fuel consumption. The lower limit for carbon footprints including these emissions are around 1 ton CO2-equivalent per capita.

For Norway, the analysis shows that Norway had more emissions embodied in imports than in exports. This is a reversal from 2001, when the emissions embodied in exports were still dominating. The reason for this is a steady increase in import volumes and associated emissions. Emissions embodied in exports remain constant over time, as we will show in a future time series analysis.

The paper by Davis and Caldeira, allowing a comparison with our numbers, underlines the importance of emissions embodied in trade. As this paper confirms, rich countries risk fooling themselves by focusing on territorial emissions while their carbon footprints are growing. The objective of climate policy should be to reduce carbon footprints, and not to reduce territorial emissions. This can only be achieved by paying attention to carbon footprints!

I am professor of industrial ecology at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

March 11, 2010