The Guardian and industry actors call for considering Carbon Embodied in Trade as part of a climate deal at Copenhagen.

On December 7, 2009, 56 newspapers from 20 countries published a joint editorial calling world leaders to use the 14 days of climate negotiations in Copenhagen in order to come to an effective and fair agreement to limit climate change.

At the time I am writing this, it is too early to see whether the call will be heeded. The editorial points correctly to what has emerged as the core element of the negotiations: the need to fairly distribute the responsibility for reducing emissions. A critical passage of the editorial, calls for recognizing the issue ofemissions embodied in trade:

Social justice demands that the industrialised world digs deep into its pockets and pledges cash to help poorer countries adapt to climate change, and clean technologies to enable them to grow economically without growing their emissions. The architecture of a future treaty must also be pinned down – with rigorous multilateral monitoring, fair rewards for protecting forests, and the credible assessment of “exported emissions” so that the burden can eventually be more equitably shared between those who produce polluting products and those who consume them.

I find it personally gratifying that the issues of forests and trade are finally being recognized, as we have spend considerable effort to raise these issues. Together with Glen Peters and Anders Stømman, I have personally worked on quantifying and modeling the emissions embodied in trade.

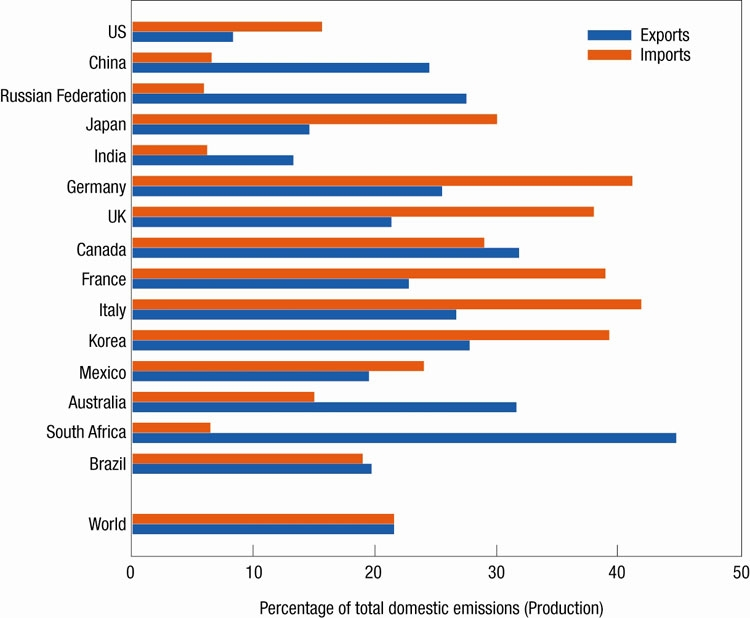

We have shown that for Norwegian household consumption, most of the carbon footprint is located abroad, where consumer goods and materials are produced. (Our calculations are now included in the official Norwegian climate calculator.) We have quantified the emissions embodied in trade for all major economies for 2001, using the same data that was also used to calculate the national carbon footprints displayed in this web page. Our results show that in 2001 more than 20% of global CO2 emission was caused by the production of exported products. The figure shows single country results from our study.

Since then, the fraction has probably increased substantially, as national-level studies suggest. My colleague Richard Wood has just updated the calculations for Norway, which indicate a dramatic growth of the emissions embodied in imports by 50% from 1999 to 2007, while emissions embodied in exports have stayed approximately constant. The changes in the emissions embodied in trade are much larger than emissions reductions due to Norway’s Kyoto target. In the UK, a similar increase in exported emissions has occurred, as results obtained by colleagues at SEI and the University of Surrey show.

Maybe the strongest evidence for the global shift in emissions is evidence from China, unearthed by Glen Peters, Dabo Guan, Chris Weber and Klaus Hubacek (Also discussed in the Guardian). Their modeling indicates that emissions embodied in export have increased from 21% of the total national emissions to 33% from 2001 to 2005, at a time when total emissions increased by 40%. Growth in emissions embodied in China’s export was the most important factor for the exceptional global emissions growth during this period.

Why does this matter? Economists argue strongly in favor of economic instruments to reduce global emissions. Carbon pricing provide an equal incentive for reducing emissions both through shifts in energy technologies, through increases in energy efficiency, and through changes in consumption patterns. We will need all these strategies to achieve climate stabilization. If, however, we have unequal carbon prices in different regions of the world, the danger is that carbon intensive production is relocated to where it is cheapest. This is, in any case, where growth is today. If that happens, gains from efficiency and structure are jeopardized.

What can be done? Most of the schemes to avoid carbon leakage and the relocation of energy-intensive industries to countries without emissions obligations are subsidy schemes: The EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) provides free emissions quotas to energy-intensive industry. There are plans to compensate the Aluminium industry directly for the high electricity price produced by the ETS. (Only from 2012, and it is not clear whether there will be any Al electrolyses left in Europe to protect.) These schemes all result in reduced costs for energy-intensive products also to consumers in carbon-limited industrialized countries and do nothing to impose the true carbon costs on imports.

The only solution that avoids these negative effects is a so-called “border tax adjustment”. This adjustment would imply that an incremental carbon tax is imposed at the border, reflecting the emissions embodied in the product imported. For most products, such a tax would be small. The global average GHG emissions per $ GDP is about 700g. A 100$/t tax implies an average 7% tax. For other products, it would be prohibitive. It would not make sense for Europe to import Aluminium produced with Chinese or South African coal power – but that is precisely the point!

I am professor of industrial ecology at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

December 14, 2009